Here’s me, telling you a little about what I do and how I work. This is the first time I’ve ever recorded a video of myself and I’m so happy to invite you all into my home, I think I’ll do more! Stay tuned.

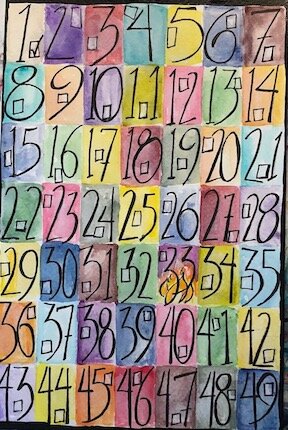

Wait. What Day is This? : Counting the Omer during a pandemic.

How appropriate to work on this omer calendar in quarantine!

The omer period commemorates the 49 days the Jews spent in the wilderness between leaving Egypt and congregating at Mt. Sinai to receive the mitzvot, instructions for how to live our lives. It is also part of the agricultural cycle. On each day of the barley harvest, the ancient Israelites brought a measurement of grain called an omer as an offering to the Temple in Jerusalem. (Leviticus 23:9-21). We single out the days because each one is a spiritual step. The Kabbalists taught us that each of the seven weeks corresponds to an aspect of The Divine.

For Jews, this is a liminal period. Some of the rituals resemble mourning, when daily life is similarly suspended and it is forbidden to listen to live music, attend parties or cut our hair. The omer is also about our collective obligation to provide food for the hungry, as it bridges Passover, when we are instructed to feed the needy through maot chitim and Shavuot, when the Book of Ruth describes the ritual of leaving grain for those who lack sustenance. Furthermore, the Torah portion of Tazriah-Metzora falls during this period, which describes how the priests checked in on the well-being of victims of a plague who were in quarantine and performed the ritual offerings on their behalf.

These directives are profoundly relevant during the Covid-19 pandemic. At least for me, sephira helps me remember what day it is, since they all seem to run into each other as I stay home, looking forward to seeing friends and family in person (let alone, getting a haircut!) But more importantly, as a human community, we can no longer ignore how many people are food-insecure, and we should donate to food pantries, meals on wheels, etc. And, like the priests in the Bible, our leaders need to tend to our most vulnerable.

Since the outbreak, a day hasn’t passed that I wasn’t moved to the point of tears by the magnitude of creativity and kindness of people all around the world whom I’m never going to meet. I’m relishing the internet rabbit hole of kooky Tik-Tok videos and news of acts of generosity, feeling awed by medical providers, appreciating teachers more than ever and am humbled by the people who deliver our stuff and stock our groceries. And I’m loving my online meetings with other artists, the weekly virtual havdalah with my Shabbat Club, and even having been part of a “Catskills at Home” night where about 100 people across the country got together on Zoom and told jokes (borscht belt in place!)

The drive to connect is profound and gives me joy even as everyone counts the days until this is over and we emerge a better, more just society. Until then, stay safe, stay healthy and stay home.

Peace,

Chana

Thoughts on Art, Jewish Education and Radical amazement

“The root of creativity is discontent with mere being, with just being around in the world.”(Abraham Joshua Heschel)

These days, I’ve been thinking about the role of the artist in our democracy and in religious life. Science and the humanities imbue the culture with openness, diversity, insight, and the liberty to express our creative selves. And when we encounter art, we find a kind of truth that transcends language. Hopefully, Jewish education and Judaic art call upon us to inquire about the nature of creation and also draw us toward holiness, love and compassion.

Art is about both curiosity and mystery. While we may think taste is all subjective, certain qualities of beauty are ever-present. Harvard psychologist Howard Gardner argues in his book Truth, Beauty and Goodness Reframed that beautiful things are by nature interesting, memorable and invite us to “revisit.” When we are drawn and re-drawn to knowledge and respect the search for truth, we are led by curiosity and the desire to describe. When ideas and images are beautiful and profound, we are moved beyond language, to an experience of awe and wonder. It is that very inability to fully articulate those experiences that makes them so beautiful.

These essential qualities also motivate spiritual exploration. When we study a Jewish text or concept, we are encouraged to “turn it over, and turn it over," mining the p’shat, text and the d’rash, interpretation. We continually ask new questions (Avot 5:21). But the beauty and awe lie in what Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel explains in his book God in Search of Man, is the sense of ineffability that is the source of religion:

"[I]n religious and artistic thinking, the disparity between that which we encounter and that which is expressed in words and symbols, no words and symbols can adequately convey. The roots of ultimate insights are found...not on the level of discursive thinking, but on the level of wonder and radical amazement, in the depth of awe, in our sensitivity to the mystery, in our awareness of the ineffable. It is the level on which the great things happen to the soul, where the unique insights of art, religion and philosophy come into being.

"[Our experience of God] is the result of wonder and radical amazement, of awe before the mystery and meaning of the totality of life beyond our rational discerning. Faith is the response to the mystery, shot through with meaning; the response to a challenge which no one can forever ignore."

For Gardner, aesthetic experience is an experience of awe. For Heschel , spiritual practice is one way to express that sense of awe. But religion doesn’t begin with intellectually trying to prove the existence of God. It doesn’t even begin with asking whether we believe in God. It begins with a moment of mystery.

Jewish education has to be linked to Jewish art in the same way that learning is suffused with mystery. So while I'm lucky to have had a Jewish education, I'm luckier to make Jewish art and share it.

Peace,

Chana

Glass Blower's Analogy

The Glass Blower’s Analogy: The Soul as a Vessel (Acrylic and Gold leaf on archival panel)

Blown glass bulb in the furnace

I took these photos at a glassblowing lesson I took in Chicago a couple of years ago. It was my first-ever attempt, and I knew the images of the glass coalescing in a furnace and the somewhat wonky vessel that resulted would one day inspire a painting. I mean, after all, glass blowing is literally the act of inspiration—from the Latin insparare, meaning ‘breathe into’ something, which is the same source as the word “spirit.” Shortly after the class, I discovered this description of the human soul from the late scholar, rabbi and physicist, Aryeh Kaplan. He drew from the 2nd-century CE foundational book of Kabbalah, the Zohar (III:25a), and the 18th-century text “The Way of God” by scholar and Kabbalist, Rabbi Moshe Hayim Luzatto, to explain:

“‘The soul of man is the ner (candle,flame) of the Lord. (Proverb (20:27). What is a ner? It is the acronym of Nefesh and Ruach… The Nefesh is bound to the Ruach, the Ruach to the Neshama, and the Neshama to the Blessed Holy One.’ The three thus form a sort of chain, linking man to God. The idea of these three parts is best explained on the basis of the verse (Genesis 2:7), ‘God formed man out of the dust of the earth, and He blew into his nostrils a breath of life.’ This is likened to the process of blowing glass, which begins with the breath (neshima) of the glassblower, flows as a wind (Ruach) through the glassblowing pipe, and finally comes to rest (Nefesh) in the vessel that is being formed. The Neshama thus comes from the same root as Neshima, meaning breath, and this is the ‘breath of God.’ The Nefesh comes from a root meaning ‘to rest’ and therefore refers to the part of the soul that is bound to the body and ‘rests’ there. Ruach means a wind, and it is the part of the soul that binds the Neshama and Nefesh.”